Opinion: Why tradition can explain cruelty but can't justify it

25 July 2017

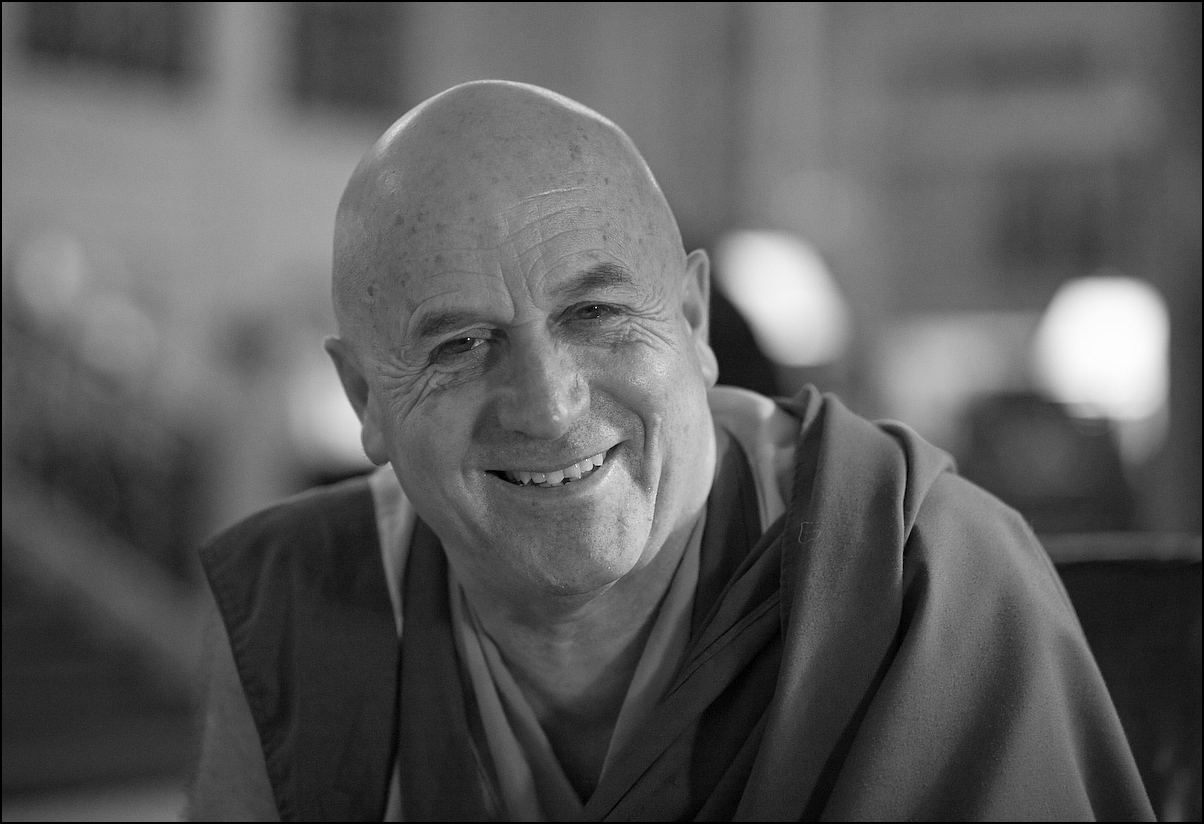

Author and Buddhist monk Matthieu Ricard writes on why we are all morally responsible for the world’s animals.

As a long-time supporter, Buddhist monk Matthieu Ricard has kindly given permission for us to publish an extract from his book “A Plea for the Animals”.

From eating habits to festivals we are told certain behaviour is acceptable because it has always been this way. Matthieu helps us to see beyond this argument and realise that while tradition can explain human activities, it cannot justify them.

Killing and Eating Animals is Part of Our Ancestral Traditions

And extract from A Plea for the Animals

By Mattieu Ricard

In Nepal, where I live, hundreds of thousands of animals, indeed some years millions, are sacrificed in a bloody manner to invoke the favour of local deities. In 2010 the appeals of a few NGOs and groups of citizens to abandon these rituals aroused groundswells of indignation, and some of the Nepalese ministers objected that this was an “ancestral tradition” that was beyond challenge. In France, one of the arguments of the manufacturers of pate de foise gras as well as of the bullfighting aficionados is that these are traditions that must be kept alive.

Traditions? How lovely! The Aztecs sacrificed as many as forty persons a day to the sun god. Human sacrifice peristed for long periods among the Hebrews, the Greeks, in Africa, and in India. The Phoenicians sometimes used to burn their own children alive in order to placate the god Baal. Onlookers have spoken with enthusiasm of this kind of killing, saying that “it was a good thing to do.” Is it not the natural property of a civilised society to abandon a tradition when it is the source of this kind of suffering?

The philosopher Martin Gibert points out: “It is thus of little importance whether the human being is related to carnivores or herbivores. The length of our intestines or of our canine teeth is a fact of evolution: it cannot determine what is morally acceptable or reprehensible for us to eat. The question is no: “can a cheeseburger be properly digested?” The question is not: “Would your ancestors have eaten it?” The question is: “Is it morally proper; should you order it?” The fact that humans are in the habit of eating meat is not an ethical argument. It is a simple fact that tells us nothing whatever about its moral worth. Tradition can explain things, but it cannot justify anything.

For the French, the traditions of the corrida and of foie gras are part of our patrimony: the cultural patrimony in the first case, the gastronomic patrimony in the second. The production of foie gras is an ordeal for the geese and the ducks. Atter having been raised for a time out in the open, the latter are usually shut up in tiny individual cages. Twice a day a hose is forced down their gullets, and in just a few seconds around a pound of thick much is injected under pressure into their esophagi. It could be compared to forcing an adult human to ingest fifteen and a half pounds of noodles twice a day. The weight of their livers goes from just over a tenth of a pound to nearly a pound and a half in twelve days. This could not happen without causing a variety of ailments: diarrhea, difficult breathing, lesions of the sternum, fractures – to the point where, according to the breeders themselves, the period of force-feeding brings about eight times more deaths than the breeding period preceding it.

On the occasion of a debate in the French National Assembly in 2006 on a law intended to protect the foie gras industry, one deputy denounced the “infernal animal welfare machine that dismantles traditions that are our traditions, especially in the South of France.” Infernal for whom? Doubtless for the stomach of the gourmets and for the wallets of the breeders, but certainly not for the animals that are being abused.

Thus we conclude that most of the reasons put forward to justify our societies’ lack of consideration for animals boil down to nothing more than sorry excuses, contrived to efface our scruples and to allow us to continue to exploit and mistreat animals with an untroubled conscience.

Matthieu Ricard is a Buddhist monk who has lived in the Himalaya for the last forty years. He earned a Ph.D. in cell genetics at the Pasteur Institute under Nobel Laureate Francois Jacob and is the author of several books including Altruism : The Power of Compassion to Change Yourself and the World and A Plea for the Animals.

BACK