One Life: Pangolins

20 February 2021

Scaly anteaters

Pangolins, also known as scaly anteaters, are unique mammals that are covered in hard, plate-like scales. They are insectivorous (feeding on insects) and are mainly nocturnal, remaining in their burrows during the day and coming out to hunt at night.

Their scales protect them from predators, but sadly they cannot protect them from humans, and they are one of the most illegally trafficked mammals in the world.

Pangolins have small heads, long snouts, and even longer tongues. They use these to suck up ants from their nests, which is why they are often referred to as scaly anteaters. They can eat up to 20,000 ants in one day!

They have very strong tails, and some pangolin species live in trees and use their tails as a fifth limb, as it is strong enough to support their full bodyweight.

Pangolin species

There are eight pangolin species, four Asian, and four African. All species are threatened with extinction, and two of the Asian species are Critically Endangered.

Little is known about the behaviour and biology of pangolins, as they are highly secretive and shy animals.

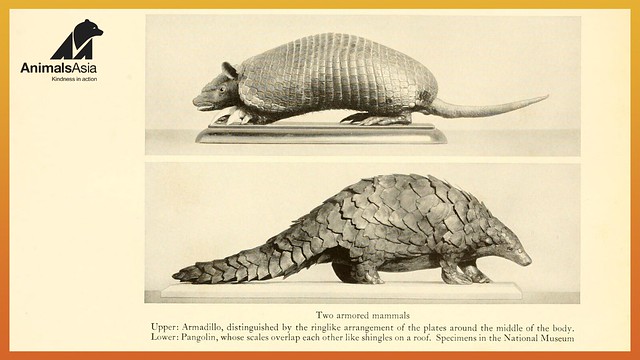

Scaly mammals

Pangolins are covered in horny, sharp and overlapping scales, these are all over them apart from on the sides of their faces, their inner legs, throat and belly. Their scales keep growing throughout their lives, though they are ground down when they dig and burrow for food.

Pangolins’ scales are made of keratin, the same protein that makes up our own hair and nails, rhino horns, the “teeth” of baleen whales, and the claws of bears (and other clawed animals). Their scales cover the entire body from head to tip of tail — except for their undersides, which are covered with a few sparse hairs.

Baby pangolins are born with soft scales, which harden after a couple of days. They ride on their mothers’ backs till they wean at around 3 months, and so are well protected.

The name, “pangolin”, is derived from the Malay word “pengguling”, which loosely translates to “something that rolls up”. When pangolins feel threatened, they curl up into a tight, almost impenetrable ball to protect their tender undersides. If caught, they will thrash about using their tail muscles. Because their scales have very sharp edges, they can slice the skin of a human or predator when they do this. They will also release a stinky fluid from a gland at the base of their tail as a defence mechanism too.

When they are feeding on their favourite food, ants and termites, pangolins have some clever adaptations.

They use their keen sense of smell to locate termite and ant nests, then they use their large and elongated claws to excavate the nests. When they do this though, they close their nostrils and ears using strong muscles to protect them from the biting ants.

Large salivary glands coat their tongues with gummy mucus, and they use this to ‘stick’ the ants and termites to the tongue before consuming them. They also possess a tongue which can extend as long as their body to help them to reach deep into nests and consume their prey.

In most species, their tongues actually start deep in their chest cavity, arising from the last pair of ribs, and are about a quarter inch (0.6 cm) thick.

Pangolins do not have teeth, and so they cannot chew their food. Instead, the insects they eat are broken up by stones and keratin spines inside their stomachs.

A single pangolin consumes as much as 70 million insects per year.

Nature’s recyclers

Pangolins play a crucial role in ensuring forest soils remain nutrient rich, and thus whole ecosystems remain healthy due to their natural behaviours. Their burrowing and excavating behaviours mix and aerate the soil —much like what happens when we turn the soil in our gardens or plough crop fields.

This improves the nutrient quality of the soil and aids the decomposition cycle, providing a healthy substrate for lush vegetation to grow from. When abandoned, their underground burrows also provide habitat for other animals.

This natural behaviour makes the Pangolin one of the ultimate natural recyclers and one of the most important members of the natural community to ensure the continued health of the forests in which they live.

Pangolins really are amazing animals!

Pangolin conservation

The biggest threat to all pangolin species today is illegal, commercial hunting for human consumption. A taste for wild meats such as pangolins in tropical and subtropical regions, makes the emergence of another global pandemic increasingly likely.

African species are largely hunted as bushmeat, but there also seems to be some regional use of their scales and other body parts in folk medicines and cultural traditions and rituals.

In China and Vietnam (the primary sources of demand for pangolins), the flesh of both adults and fetuses is considered a delicacy and some mistakenly believe they will be blessed with health benefits if they eat it. Their scales, blood, and other body parts are also widely used in traditional Chinese medicines (TCMs) and ‘health tonics’. There is mounting concern that African pangolins are being targeted to supply the burgeoning Far East demand for these animals, as Asian species’ populations continue to plummet toward extinction.

Despite the fact that scientific studies have proven that keratinous body parts of other animals (e.g. rhino horns) are void of any medicinal or curative properties, many continue to consume pangolin scales as a TCM remedy for a wide variety of health problems, such as reducing swelling, promoting blood circulation, and stimulating lactation in breastfeeding women.

More recently, rumors likely spawned by Chinese pangolin “farming” business ventures have falsely claimed pangolin-derived TCMs can even cure cancer. As a result of the black market demand for these animals, an estimated 41,000-60,000 pangolins were plundered from the wild in 2011 alone.

The most trafficked animal in the world

Some species of pangolins are Critically Endangered, and all species are at least Vulnerable. The IUCN estimates that a pangolin is taken from the wild every 5 minutes. Their populations simply cannot sustain this, and they will soon be extinct if this continues.

In April 2019, two shipments of pangolins were seized with 28 tonnes of pangolin scales between them. This was thought to have been taken from around 72,000 pangolins! Last month Animals Asia’s partner organisation Flight: Protecting Indonesia's Birds initiated a raid of an illegal wildlife trader who had 4.7kg of scales for sale.

The Chinese and the Sunda pangolins are the most endangered of all eight species. In the case of the latter, their numbers began to decline quite rapidly around 1990 and the population has halved over just the last 15 years. The IUCN reports that Chinese pangolins have also been greatly reduced over this time period. Despite being protected by CITES, poaching is decimating these (and other) species/

Pangolin welfare:

To harvest pangolin scales, the pangolin must be killed first. To do this, hunters will cut down their trees or smoke them out with fire. The pangolins will lose consciousness as they suffocate from the smoke, and the hunters capture and bag them, taking them away for processing.

This process means that poachers can harvest and trade the pangolin’s scales. Unfortunately, the pangolin experiences considerable pain and suffering as a result. These incredible wild animals do not deserve this.

Read more:

Thousands of illegally trafficked Indonesian songbirds rescued and released

Jill’s Blog: Healing without harm.

BACK